The (African) Arab Cup

Morocco’s World Cup heroics are forging a new, dissident Third-World solidarity, reflecting the multifaceted nature of Moroccan identity itself: simultaneously Arab, African, and Amazigh.

7 Article(s) by:

Hisham Aïdi is Senior Lecturer at SIPA Columbia University and a scholar-in-residence at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, working on a project titled W.E.B. Du Bois and the Afro-Arab World.

Morocco’s World Cup heroics are forging a new, dissident Third-World solidarity, reflecting the multifaceted nature of Moroccan identity itself: simultaneously Arab, African, and Amazigh.

Why did North Africans and Middle Easterners almost overnight go from being comrades-in-struggle to racial intruders in Africa and in African American cities?

Anti-racism and political contagion from Save Darfur to Black Lives Matter.

The long and wondrous life of Hassan Ouakrim, the “Cultural Ambassador” of the Maghreb to the United States.

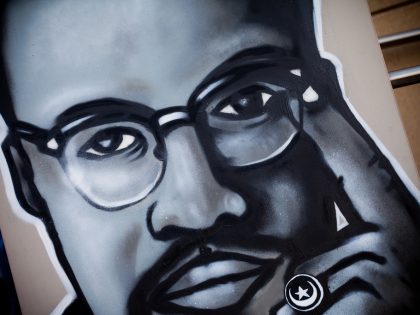

Malcolm X is a powerful optic through which to understand America’s post-war ascendance and expansion into the Middle East.

The legacy in Morocco of the influential Spanish-born novelist Juan Goytisolo, who died in mid-2017.

A image of Muyal with "Juice Wilson" on the cover of a magazine. Published with permission from Jacques Muyal.[/caption]

Like most youth growing up in Tangier, Muyal tried to learn English by listening to the radio. “I listened to Conover, I studied the liner notes – and dreamt of one day meeting the artists on the album covers,” says Muyal. One evening in July 1959, he was walking down Boulevard Pasteur and saw four black men walk past him. “I thought – I’ve seen that face somewhere.” He ran after them, and tapped one of them on the shoulder, “Aren’t you Idriss Sulieman?” Sulieman smiled and raised both hands like he was being arrested.

Muyal had recognized the musician from a Monk album cover -- Sulieman was one of the first trumpeters to play with the pianist. The other three musicians were pianist Oscar Dennard, bassist Jamil Nasser and drummer Buster Smith. The musicians had traveled to Tangier, looking for gigs and musical inspiration, but also for religious reasons. With the collapse of the Garveyite movement in the 1930s, many politically active African Americans had gravitated towards the Nation of Islam and the Baha’i movement. Tangier is home to myriad Sufi shrines and brotherhoods, and at 20 miles from the Spanish coast, it was the closest point of the Muslim world for American converts visiting Europe. But also, in the mid-1950s, a small Baha’i community had formed in Tangier, led by Helen Elsie Austin, an American foreign service officer teaching at the newly founded American School. [Incidentally, Gillespie would end up converting to Bahaism and reflecting Baha’i teachings name his band “The United Nation Orchestra,” Muyal would in jest often tell him, “you really should have called your band the Tangier Orchestra, because it’s in Tangier where the nations of the world converge."]

“They came looking for Islamic spirituality,” says Muyal, “Idriss Sulieman was one of the first converts to Islam, Oscar Dennard was also Muslim – his [Muslim] name was Zain Mustapha.” Muyal would book the musicians for a three-month stint at the Russian-owned Casino de Tanger, where they performed as the “4 American Jazzmen in Tangier.” But before that he invited them to the studio at Radio Tanger, where he recorded an impromptu session. “We had a badly tuned upright piano,” recalls Muyal, “I didn’t have money for a band (tape), so I just glued together some tape from broken reels we had.”

After Tangier, the jazzmen traveled to Tunis and then Cairo, where the 30-year old Dennard contracted typhoid and died. He would be buried at Zein Eldin cemetery in the Egyptian capital, his grave for many years a stop for jazz musicians visiting Egypt. This enigmatic, self-effacing Memphis-born prodigy who had played regularly with Lionel Hampton was widely admired for his dazzling style, but he left no recordings behind – except for the impromptu session at Radio Tanger. And that is the recording that Muyal released earlier this year. In the early 1970s Muyal stumbled upon the tape and sent cassette copies to some of his pianist friends – Cedar Walton, Billy Higgins, McCoy Tyner – the word spread and soon his phone was ringing off the hook.

“Oscar was a prodigy, he was the inspiration for Ahmed Jamal and Harold Mayborn – listening to him it’s hard to believe that there are only two hands playing,” says Muyal, “But I never thought it would become a historic recording.” The recent release “4 American Jazzmen in Tangier: Idress Sulieman Quartet featuring Oscar Dennard” is two discs: the first is the RTI session recorded in 1959, and the second a recording that Jamil Naser sent to Muyal, 45 years ago, of Sulieman’s quartet and Oscar Dennard playing at a party in Quincy Jones’s Manhattan apartment in early 1959, just before they traveled overseas. The audio of the second tape was not high quality, but new technology has allowed Muyal to shore up the sound. On the Tangier recording one can hear the echo of a small studio and the poorly-tuned piano, but Dennard’s scintillating touch and Sulieman’s mournful trumpet make for a crisp, intimate, bluesy sound.

Tangier occupies a curious role in the American jazz imagination. Tune in to WBGO, New York’s only jazz station, on any weekday morning and at some point you’ll hear whirling wind, faint drums and a voice over, “Imagine yourself in Tangiers [sic] … listening to “Morning Jazz,” as sand blows against wind screens.” Compositions named for the city abound – Idrees Sulieman’s “Tangier Blues,” Herbie Mann’s “In Tangier,” Randy Weston’s “Tangier Bay,” Ornette Coleman’s “Interzone Suite,” Carol Robbin’s “Tangier,” Hot Jazz Club “Swing de Tangiers.”

In the mid-1950s, the eminent jazz critic Albert Murray, then a young captain stationed at the Nouasser air base in Casablanca, delivered a series of lectures (in French) on the meaning of jazz. He stressed that the art form was the creation of the “black American” – l’Américain d’Afrique – adding rather cryptically that “jazz in Africa does not exist, with the exception of Lionel or Armstrong, when they come to Tangier, Casablanca or Marrakesh.”

It’s not clear what the meaning of Tangier is to jazz aficionados and artists – a triumph of American ascendency, escape from western society, an African wellspring – but a succession of jazz artists have spent time in Tangier, from Josephine Baker and Ted Joans to Archie Schepp and Ornette Coleman. And it’s fair to say that the city would not have gained such a prominent place in the jazz world were it not for the half-century partnership between Muyal and pianist Randy Weston. Based respectively in Geneva and Brooklyn, they brought the sounds of Morocco – particularly Gnawa music – to jazz audiences. When Algeria organized its pan-African music festival in 1969, Weston, in response, organized the first pan-African jazz festival in Tangier in June 1972 that brought Dexter Gordon, Kenny Drew, Billy Harper, Odetta, Pucho and the Latin Soul Brothers and others to the Teatro Cervantes. Weston’s festival would become the inspiration for the multiple jazz festivals now organized year-round in Morocco.

After high school, Muyal moved to Paris for university, but almost failed out, as he was also working late nights as a jazz promoter. So he moved Geneva, where he earned a degree in sound engineering from the prestigious École Polytechnique in Lausanne. In the mid-1970s, with the rise of the Fania All Stars, he would become a critical link between Europe and the world of Latin jazz, going on to produce documentaries for Spanish television on saxophonist Paquito d’Rivera and the music scene in Havana. (His most recent Latin jazz record is a gem of bossa nova piano, titled Kenny Barron and the Brazilian Knights (recorded in Rio in 2012).

[caption id="attachment_100616" align="alignnone" width="672"]

A image of Muyal with "Juice Wilson" on the cover of a magazine. Published with permission from Jacques Muyal.[/caption]

Like most youth growing up in Tangier, Muyal tried to learn English by listening to the radio. “I listened to Conover, I studied the liner notes – and dreamt of one day meeting the artists on the album covers,” says Muyal. One evening in July 1959, he was walking down Boulevard Pasteur and saw four black men walk past him. “I thought – I’ve seen that face somewhere.” He ran after them, and tapped one of them on the shoulder, “Aren’t you Idriss Sulieman?” Sulieman smiled and raised both hands like he was being arrested.

Muyal had recognized the musician from a Monk album cover -- Sulieman was one of the first trumpeters to play with the pianist. The other three musicians were pianist Oscar Dennard, bassist Jamil Nasser and drummer Buster Smith. The musicians had traveled to Tangier, looking for gigs and musical inspiration, but also for religious reasons. With the collapse of the Garveyite movement in the 1930s, many politically active African Americans had gravitated towards the Nation of Islam and the Baha’i movement. Tangier is home to myriad Sufi shrines and brotherhoods, and at 20 miles from the Spanish coast, it was the closest point of the Muslim world for American converts visiting Europe. But also, in the mid-1950s, a small Baha’i community had formed in Tangier, led by Helen Elsie Austin, an American foreign service officer teaching at the newly founded American School. [Incidentally, Gillespie would end up converting to Bahaism and reflecting Baha’i teachings name his band “The United Nation Orchestra,” Muyal would in jest often tell him, “you really should have called your band the Tangier Orchestra, because it’s in Tangier where the nations of the world converge."]

“They came looking for Islamic spirituality,” says Muyal, “Idriss Sulieman was one of the first converts to Islam, Oscar Dennard was also Muslim – his [Muslim] name was Zain Mustapha.” Muyal would book the musicians for a three-month stint at the Russian-owned Casino de Tanger, where they performed as the “4 American Jazzmen in Tangier.” But before that he invited them to the studio at Radio Tanger, where he recorded an impromptu session. “We had a badly tuned upright piano,” recalls Muyal, “I didn’t have money for a band (tape), so I just glued together some tape from broken reels we had.”

After Tangier, the jazzmen traveled to Tunis and then Cairo, where the 30-year old Dennard contracted typhoid and died. He would be buried at Zein Eldin cemetery in the Egyptian capital, his grave for many years a stop for jazz musicians visiting Egypt. This enigmatic, self-effacing Memphis-born prodigy who had played regularly with Lionel Hampton was widely admired for his dazzling style, but he left no recordings behind – except for the impromptu session at Radio Tanger. And that is the recording that Muyal released earlier this year. In the early 1970s Muyal stumbled upon the tape and sent cassette copies to some of his pianist friends – Cedar Walton, Billy Higgins, McCoy Tyner – the word spread and soon his phone was ringing off the hook.

“Oscar was a prodigy, he was the inspiration for Ahmed Jamal and Harold Mayborn – listening to him it’s hard to believe that there are only two hands playing,” says Muyal, “But I never thought it would become a historic recording.” The recent release “4 American Jazzmen in Tangier: Idress Sulieman Quartet featuring Oscar Dennard” is two discs: the first is the RTI session recorded in 1959, and the second a recording that Jamil Naser sent to Muyal, 45 years ago, of Sulieman’s quartet and Oscar Dennard playing at a party in Quincy Jones’s Manhattan apartment in early 1959, just before they traveled overseas. The audio of the second tape was not high quality, but new technology has allowed Muyal to shore up the sound. On the Tangier recording one can hear the echo of a small studio and the poorly-tuned piano, but Dennard’s scintillating touch and Sulieman’s mournful trumpet make for a crisp, intimate, bluesy sound.

Tangier occupies a curious role in the American jazz imagination. Tune in to WBGO, New York’s only jazz station, on any weekday morning and at some point you’ll hear whirling wind, faint drums and a voice over, “Imagine yourself in Tangiers [sic] … listening to “Morning Jazz,” as sand blows against wind screens.” Compositions named for the city abound – Idrees Sulieman’s “Tangier Blues,” Herbie Mann’s “In Tangier,” Randy Weston’s “Tangier Bay,” Ornette Coleman’s “Interzone Suite,” Carol Robbin’s “Tangier,” Hot Jazz Club “Swing de Tangiers.”

In the mid-1950s, the eminent jazz critic Albert Murray, then a young captain stationed at the Nouasser air base in Casablanca, delivered a series of lectures (in French) on the meaning of jazz. He stressed that the art form was the creation of the “black American” – l’Américain d’Afrique – adding rather cryptically that “jazz in Africa does not exist, with the exception of Lionel or Armstrong, when they come to Tangier, Casablanca or Marrakesh.”

It’s not clear what the meaning of Tangier is to jazz aficionados and artists – a triumph of American ascendency, escape from western society, an African wellspring – but a succession of jazz artists have spent time in Tangier, from Josephine Baker and Ted Joans to Archie Schepp and Ornette Coleman. And it’s fair to say that the city would not have gained such a prominent place in the jazz world were it not for the half-century partnership between Muyal and pianist Randy Weston. Based respectively in Geneva and Brooklyn, they brought the sounds of Morocco – particularly Gnawa music – to jazz audiences. When Algeria organized its pan-African music festival in 1969, Weston, in response, organized the first pan-African jazz festival in Tangier in June 1972 that brought Dexter Gordon, Kenny Drew, Billy Harper, Odetta, Pucho and the Latin Soul Brothers and others to the Teatro Cervantes. Weston’s festival would become the inspiration for the multiple jazz festivals now organized year-round in Morocco.

After high school, Muyal moved to Paris for university, but almost failed out, as he was also working late nights as a jazz promoter. So he moved Geneva, where he earned a degree in sound engineering from the prestigious École Polytechnique in Lausanne. In the mid-1970s, with the rise of the Fania All Stars, he would become a critical link between Europe and the world of Latin jazz, going on to produce documentaries for Spanish television on saxophonist Paquito d’Rivera and the music scene in Havana. (His most recent Latin jazz record is a gem of bossa nova piano, titled Kenny Barron and the Brazilian Knights (recorded in Rio in 2012).

[caption id="attachment_100616" align="alignnone" width="672"] Oscar Dennard and his quartet in Tangier. Published with permission from Jacques Muyal.[/caption]

Muyal began traveling regularly to North America. In the US, he found a mentor and kindred spirit in Norman Grantz, the founder of Verve Records, who had sought to use jazz to break down segregation. Muyal’s ability to move effortlessly between identities and communities fascinated his jazz associates – much to his amusement. D’Rivera dubbed him the “Afro-Swiss;” poet Ted Joans would call him “afrospanishjewishmoroccan music/hipster.” The great pianist Bud Powell would regularly ask: “So Jack, you’re from Tangier right? So does that make you a Moor? You’re sure you’re not a Moor?

Muyal grew closest to Dizzy Gillespie, and would take time off work to accompany the trumpeter on his tours around the world. After the shows, he would crash in Gillespie’s suite. When in New York, he would stay in Gillespie’s home in Englewood, New Jersey. “Lorraine [Gillespie’s wife] wouldn’t let anyone stay over,” laughs Randy Weston, “And yet this Tangier cat would spend weeks at their house.”

In the documentary, Muyal speaks emotionally about Gillespie’s final days at the hospital, how the musician would beckon his doctors by clapping his hands as he did on stage to direct his band members. When Dizzy, propped up in a chair, drew his last breath, Muyal carried him to his bed. An hour later he called in an article to Jazz Magazine in Paris – “The Bluest Blues,” a tribute to his friend -- that was included in the publication’s 100-year anniversary volume.

When not touring the world and being feted like an elder statesman, he returns to his duplex apartment on Lake Geneva. At the entrance to his office hangs a small, intricately-carved bronze lamp, a Moroccan hannukiah, passed down through the Muyal family. Inside one sees a drum set, the various Nagra recorders and weight scales he designed, a framed album cover of Norman Grantz’s first concert at the New York Philharmonic – and lots of Dizzy paraphernalia (Dizzy’s bent trumpet, his necklace-medallion, framed photographs of the be-bopper in Paris, a poster of Dizzy’s film “A Night in Havana,” and so on.) On the book shelf behind Muyal’s desk sits a volume, a Spanish translation of Marshall Stearn’s classic The Story of Jazz (1956), which he was awarded as a prize for his translations of Conover’s show.

“Jazz has taken me around the world. From Japan to Uruguay and back to Morocco,” says Muyal picking up the book, “I dreamed a life and I lived it. I say it’s the baraka of Tangier.”

Oscar Dennard and his quartet in Tangier. Published with permission from Jacques Muyal.[/caption]

Muyal began traveling regularly to North America. In the US, he found a mentor and kindred spirit in Norman Grantz, the founder of Verve Records, who had sought to use jazz to break down segregation. Muyal’s ability to move effortlessly between identities and communities fascinated his jazz associates – much to his amusement. D’Rivera dubbed him the “Afro-Swiss;” poet Ted Joans would call him “afrospanishjewishmoroccan music/hipster.” The great pianist Bud Powell would regularly ask: “So Jack, you’re from Tangier right? So does that make you a Moor? You’re sure you’re not a Moor?

Muyal grew closest to Dizzy Gillespie, and would take time off work to accompany the trumpeter on his tours around the world. After the shows, he would crash in Gillespie’s suite. When in New York, he would stay in Gillespie’s home in Englewood, New Jersey. “Lorraine [Gillespie’s wife] wouldn’t let anyone stay over,” laughs Randy Weston, “And yet this Tangier cat would spend weeks at their house.”

In the documentary, Muyal speaks emotionally about Gillespie’s final days at the hospital, how the musician would beckon his doctors by clapping his hands as he did on stage to direct his band members. When Dizzy, propped up in a chair, drew his last breath, Muyal carried him to his bed. An hour later he called in an article to Jazz Magazine in Paris – “The Bluest Blues,” a tribute to his friend -- that was included in the publication’s 100-year anniversary volume.

When not touring the world and being feted like an elder statesman, he returns to his duplex apartment on Lake Geneva. At the entrance to his office hangs a small, intricately-carved bronze lamp, a Moroccan hannukiah, passed down through the Muyal family. Inside one sees a drum set, the various Nagra recorders and weight scales he designed, a framed album cover of Norman Grantz’s first concert at the New York Philharmonic – and lots of Dizzy paraphernalia (Dizzy’s bent trumpet, his necklace-medallion, framed photographs of the be-bopper in Paris, a poster of Dizzy’s film “A Night in Havana,” and so on.) On the book shelf behind Muyal’s desk sits a volume, a Spanish translation of Marshall Stearn’s classic The Story of Jazz (1956), which he was awarded as a prize for his translations of Conover’s show.

“Jazz has taken me around the world. From Japan to Uruguay and back to Morocco,” says Muyal picking up the book, “I dreamed a life and I lived it. I say it’s the baraka of Tangier.”