The linguistic famine

The burial of African languages by Africans themselves has ensured our total immersion into colonial culture.

Nick Owuor, via Unsplash.

We all know Kenyans who, after a short stint in the United States, come back home with a mangled American accent—the kind you know is put on or forced and which makes you cringe because you know how much effort it has taken for the speaker to develop it.

It makes you wonder what it is about America that makes people quickly put on accents that are not theirs. Is it lack of self-esteem, or is it a fervent desire to fit into White America? Do people who adopt American accents believe they have a better chance of being assimilated into American society? Or do they believe that they can only move ahead in their careers if they are better understood by their American audiences? Is changing one’s accent a route to career advancement?

The Sri Lankan journalist Varindra Tarzie Vittachi wrote about this phenomenon in his book The Brown Sahib, in which he describes post-colonial Indian administrators and top-level civil servants who became mere caricatures of the British and Britishness when the colonialists left India. Eager to please their former masters, they went to great lengths to adopt British accents and mannerisms—not realizing that: a) they could never pass off as British no matter how hard they tried, and b) by denigrating their own language and culture, they generated even more contempt for themselves among the British, who viewed them as mimicking buffoons who had no dignity or respect for their own culture and identity.

I lived in the United States for five years when I was a student there, but did not come home with an American accent. I think it’s partly because I am multilingual (I’ll explain why this matters later) and also because I don’t like the loud nasal screechy tone of American accents. I find the accent off-putting. It lacks the subtle sensuality of French, the lyricism of Urdu or the sophistication of coastal Kiswahili.

Later on, when I worked in the diverse multicultural environment of the United Nations, I realized that American accents were the minority, and had very little to do with career advancement, so there was no need to put them on. Though race and gender mattered when it came to getting the top management jobs, it was not rare to have a Senegalese with a heavy French-Senegalese accent heading a department or a Russian with very little knowledge of English running an IT section. Most UN staffers are valued not for their knowledge of English, but for their fluency in a variety of languages. So speaking English with an American accent was hardly a plus point.

Kenyans who develop American accents overnight remind me of something Sharmila Sen, an American writer of Indian origin, wrote. In her recently published book, Not Quite Not White, Sen talks about how she used to rehearse speaking with an American accent when her family migrated to America from their native India when she was a child. Her family had moved to Boston from Calcutta and she was afraid that her Indian Bengali accent would be mocked by her classmates. So she spent hours watching American television, learning to speak like the characters in Little House on the Prairie and Dallas (probably not realizing that accents vary across America; Texans speak with a specific drawl that is quite distinct from the speech pattern of someone born and raised in New England).

When the twelve-year-old Sen arrived in America with her immigrant parents, she was fluent in three languages: Bengali, Hindi, and English. But in her almost all-white school, she pretended that she did not know any Indian language and did not even watch Indian movies, even though she loved them. She was afraid that her classmates might find out that Bengalis eat with their hands and that she would be the laughing stock of the entire school, so she never invited friends home. Her parents, keen to assimilate in their new country, insisted on using forks and knives, even though they had little desire to use them. She says she and her family didn’t want to be associated with “fresh off the boat” people in America, who fail to assimilate into American society, and live cocooned lives in ghettoes. Most importantly, she didn’t want to appear “threatening, unnatural, or ungrateful.”

She also smiled a lot, which she says is common among brown and black people living in America. As an African American man, a fellow doctoral candidate, explained to her, “We smile because it is the only face we can show. If we stop smiling, they will see how angry we are. And no one likes an angry black man.”

Sen says that as she grew older and understood white privilege, she decided to “go native” and not smile too much because she was tired of being the entertainer, the storyteller, the explainer of all things Indian to white audiences. She also did not want her sons and daughter to be viewed as “people of color” (a designation she resents).

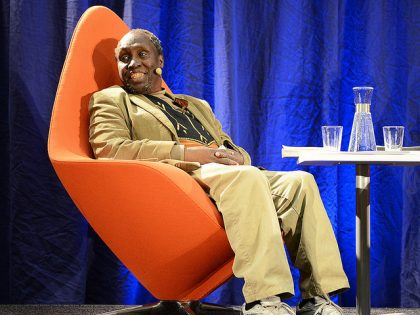

Another writer who decided to go truly native is our very own Ngũgi wa Thiong’o. In Ngũgi’s case, not only did he not adopt an American accent when he went into self-imposed exile in the US, but he decided to abandon the English language altogether in favor of his mother tongue, Gĩkũyũ. Perhaps that is why his acceptance speech for an award he received recently was entirely in his native tongue.

Ngũgi believes that when you erase a people’s language, you erase their memories. And people without memories are rudderless, unconnected to their own histories and culture, mimics who have placed their memories in a “psychic tomb” in the mistaken belief that if they master their colonizer’s language, they will own it. Because erasure of memory and culture is a condition for successful assimilation, the burial of African languages by Africans themselves has ensured their total immersion into colonial culture. He calls this phenomenon a “death wish” that occurs in societies that have never fully acknowledged their loss—like trauma victims who resort to drugs to kill the pain.

Many people of my generation are multilingual because they were encouraged to speak their mother tongue at home. While I was taught in English in school, I learned to speak and understand Hindi and Punjabi at home and picked up Kiswahili on the streets. Later, I picked up a bit of French in high school, and Urdu as well, because my father loved Urdu poetry and ghazals.

All these languages have enriched my life in ways that would not have been possible had I not learned them. Without them, I would have never been able to understand the subtle meanings and nuances embedded in certain Punjabi words. I would not have been able to communicate with my grandmother or watch and enjoy Bollywood films. Nor would I have realized that President Moi’s speeches in English were very different in meaning and tone from his speeches in Kiswahili. I would not have developed an understanding of my own and other people’s cultures or developed empathy and tolerance for other races and ethnic groups had I not been multilingual. Language is the pathway to a culture’s soul.

Sadly, the generations that come after me have abandoned their native tongue in favor of English. Some parents even encourage their children not to speak their mother tongue at home because it might “contaminate” their English accent.

At a public lecture he gave at the University of Nairobi a few years ago, Ngũgi derided Kenyan parents for discouraging their children from speaking their mother tongues, a phenomenon that has led to what he called a “linguistic famine” in African households. This would never happen in countries such as Germany or France, where German and French children learn their own language before they learn English. Nor would it happen in China, India or Brazil, all of which are emerging economies. (I have yet to meet a Chinese person who feels ashamed about not knowing English.)

Even in neighboring Tanzania and Somalia, people become fluent in Kiswahili and Somali, respectively, before they learn other languages. A few years ago, I participated in a two-day local government meeting in Dar es Salaam which was conducted in just in one language – Kiswahili. Like many Kenyans who visit Tanzania, I became painfully aware of the fact that my mastery of this beautiful language was woefully inadequate. My only (lame) excuse for this is that in my school days, Kiswahili was not a mandatory subject.

Knowledge of many languages promotes inter-cultural dialogue and understanding, and is essential in a globalizing world. If Kenyans are to be successful citizens of the world, they must learn their own and other people’s languages. And we should stop putting on accents just to impress others. Putting on an accent that is not natural is not just silly and painful to watch; it is also a sign that those who feel compelled to change their accents have a large amount of self-loathing going on, which is just plain sad.

The late Wangari Maathai said that “culture is coded wisdom”, and must be preserved. Language is one of the vehicles through which that culture is transmitted. We must preserve our languages for the sake of present and future generations.