The margins of urban life in Angola

In Angola, the poor are not entitled to full citizenship rights. They also are the base of resistance to the regime.

Image credit Paolo Pescio via Flickr (CC).

For a while now, photos have been circulating on social media—still a viable option for circumventing the official media gatekeepers—denouncing the violent treatment of informal street vendors by police in the country’s capital, Luanda. One of them showed a young girl brutally beaten by an officer and left unconscious in the street. But it was the death of Juliane Cafrique—a 28-year old street-vendor and mother of three, on March 12th—that sparked confrontations between the local population and police in Luanda’s Rocha Pinto neighborhood. There had allegedly been an argument with the police, who then shot Cafrique in front of one of her young children. The police did not call for medical assistance, instead they left the young woman in the road.

Within the hour after Juliana Cafriques’ death, videos began to circulate online of riots. Authorities expressed alarm. The historical legacy of the “shantytowns” and their perceived “volatility” have led state forces to treat residents with brutality.

Last year, the inauguration of João Lourenço as the new Angolan president brought hopes of change. Angolans applauded the sacking of government officials with close links to former President Jose Eduardo dos Santos as crucial step in Lourenço’s anti-corruption agenda. The ruling MPLA has governed Angola since independence in 1975. When Angola held its first multiparty elections in 2002, following the civil war, the MPLA continued in power.

Yet, João Lourenço’s newly envisioned program “Operação Resgate” (Operation Rescue) faces growing criticism. In the cities, particularly the capital Luanda, the program’s aim to “restore state order” targets the informal economy, eliminating what urban officials denote as the “chaos” that comes with the circulation of “illegal products” and women street vendors. Critics also argue that Operação Resgate aligns itself closely with the MPLA’s state-building agenda to make Angola a “modern, cosmopolitan state.” The program prioritizes an elitist vision of the city to attract foreign investment, often at the expense of the urban poor.

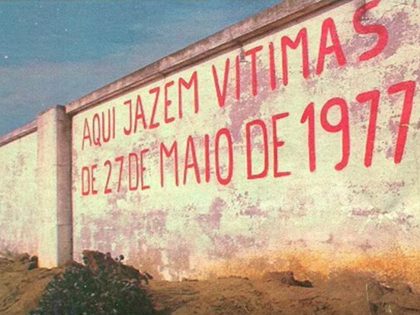

For years there has been relative stability around the Angolan shantytowns, or “musseques,” where an estimated 90% of Luanda’s population live. This is mostly the consequence of a self-censorship that ensued after decades of conflict, and the uncertainty that surrounds the events May 27th of 1977—when thousands were killed after an alleged coup d’état. The event remains taboo in Angolan socio-political life—and its traumatic memory still lingers in the Angolan psyche.

Today, fears of social unrest have meant the party-state keeps an eye trained on these urban spaces. The state attempts to infiltrate the shantytowns through civil society organizations, or through the financing of sporting and musical (namely kuduro) events. Kuduro, one of the most popular Angolan music genres amongst the youth—has been predominantly co-opted by the MPLA since its inception in the 1990s. Corean Du, the former president’s son is in charge of the bulk of its production line in Angola—endorsing some of the genre’s most popular musicians in the shantytowns. In return, these artists become staunch supporters of the party, at times using nationalist motifs in their music and image—with their popularity being broadcast on state TV channels. Today, a belief persists that affiliation to the party is an important guarantor to self-sufficiency in the music sphere.

Since 2011, an increasing number of protests have marked a new point in Angolan political life. Today, in the face of promises of oil-driven growth by the government, there is a growing resentment to the indifference with which the lives of the poor are treated.

Zungueiras, female street vendors, are symbols of the marginalized urban poor. The name derives from the Kimbundu word zunga, which means to “wander, circulate.” In very many cases, they are the primary breadwinners in their families. This was the case for Juliana, whose husbands’ unemployment had made her the primary caregiver and earner in her family.

This has become a familiar narrative in a country where economic fragility and plunging oil prices have considerably reduced employment opportunities—especially for the majority who have not had access to education.

Juliana: woman, mother and wife—stands for hundreds of others in Angola’s urban margins who continue to face discrimination and harsh living conditions—and yet continue to assert themselves in their fight for survival. Like many other zungueiras, Juliana had migrated from one of Angola’s interior provinces in search of better living standards in the capital.

Today, Operation Rescue should be understood in light of the government’s desire to build a “world-class city”—often branded in media channels and policy documents as the construction of a new Dubai. The daily use of space by women street vendors in Angola’s streets, is not in harmony with the states’ yearning for “progress.”

Several academics have noted the way in which this practice of post-war reconstruction has been predominantly a mode of solidifying MPLA political and economic control. The government’s aesthetics of modernization, in the form of shopping malls, high rises and luxury condominiums predominantly bypass the poor who are perceived as irregular occupants of the city.

Ultimately, Juliana Cafrique’s death should be understood within a wider governmental plan that perceives as an obstacle those who do not “assimilate” within the MPLA’s conception of a modern state. The war is now an increasingly distant memory for Angola’s predominantly young generation. Continuously confronted with evident urban and economic segregation, resistance is bound to thrive in unexpected ways as people contest the incongruences of a government rhetoric that continues to perpetuate dynamics of exclusion.

The death of Juliana Cafrique raises an uncomfortable truth in Angola: not everyone is entitled to full citizenship rights. Yet, today, it seems that Angolans will continue to reclaim their rights to citizenship and to the city—moving from the margins of urban political life.