Racial Degeneracy and Cowardice

The failure of Americans to have a concerted conversation on racism is not surprising. Too much is at stake for too many people, interests and institutions.

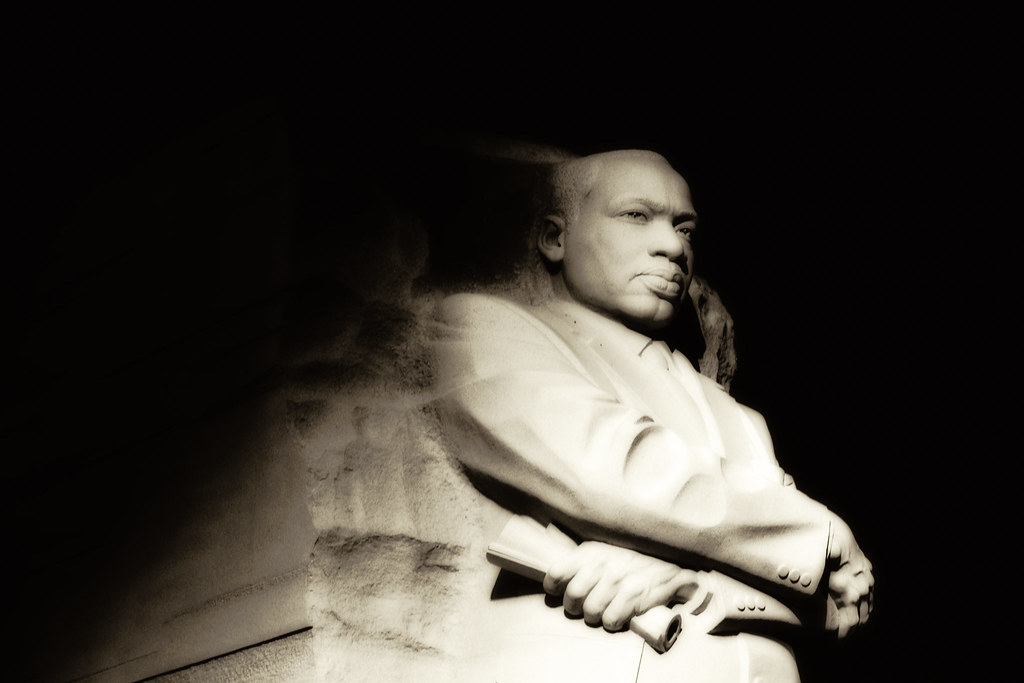

Image by Johnny Silvercloud, via Flickr CC.

The names are added to the long hall of infamy with sickening, stultifying regularity. The latest include Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, and all those black boys and men sacrificed at the altar of America’s racism, the country’s enduring original sin. Each generation of Americans is confronted by the ugly face of this primordial transgression, its staying power, its infinite capacities to make a mockery of the country’s vain self-congratulation as the land of freedom, democracy, and the rule of law. Proclamations that fall on deaf ears to its minority citizens and the outside world that experience and see the hypocrisies, contradictions, and inconsistencies spawned by the destructive deformities of racism.

The degeneracy of American racism runs deep, rooted in more than two centuries of slavery, the foundational matrix of American society, economy, and politics. It was renewed and recast during a century of Jim Crow. It survived and mutated over the last half century of civil rights. It persists in the Obama era, confounding misplaced expectations for a post-racial society that the election of the country’s first black president was magically supposed to usher in.

Each generation of African Americans faces eruptions of this racial degeneracy, most tragically captured in deadly assaults against unarmed black males by the police that predictably provoke widespread local and national protests. Each moment acquires its symbols and slogans. This year it’s Ferguson and the battle cry “Hands Up Don’t Shoot” and New York and Eric Garner’s plaintive cry for life, “I can’t Breath.” Both have become rallying anthems of protests across the nation following the grand jury decisions not to indict the police officers that killed the two men.

Outrage is often centered on the altercations between the law enforcement agencies and African American communities because of the racial disproportionalities in surveillance, profiling, arrests, and sentencing. Mountains of data show African Americans are subject to forms of policing that are far more excessive, abusive, and disrespectful than European Americans. This has resulted in the creation of an American gulag of black imprisonment, a prison pipeline especially for black males from the schools, streets, and sidewalks of America.

The broken relations between African American communities and law enforcement agencies and the exponential growth of a black prison industrial complex in the era following the civil rights struggles represent the contemporary forms of America’s age-old racial structures, hierarchies, and ideologies, the country’s new Jim Crow regime of existential, economic and epistemic violence against black lives, black well-being, and black citizenship.

Police brutality and unaccountability for violence against African Americans is facilitated by and a manifestation of the wider society’s values, expectations, and interests. The challenge is not simply to provide the police with better training or technologies, although that would help. Lest we forget, Eric Garner’s death was captured on video, and the grand jury still refused to indict the policeman. In a bygone era, public lynchings were spectacles of morbid public entertainment. The real issue is the value placed on black lives, black bodies, and black humanity by American society.

The discourse by the police and their supporters often taps into persistent racial codes: the bodies of the black victims are full of brawn, not brains, depicted as embodiments of some fearsome bestial power that threaten their police interlocutors, which can only be tamed by superior weapons and intelligence. The police officer who killed Michael Brown described the latter as an overpowering Hulk Hogan “demon” who “grunted” and charged at him like a mindless animal. A Republican Congressman blamed Eric Garner for his own death, saying “If he had not had asthma, and a heart condition, and was so obese, he would not have died from this.” And 12 year-old Tamir Rice was mistaken for a 20 year old, a homage to the black man-child stereotype of racial discourse in white supremacist America and colonial Africa.

Each generation of Americans is forced to reckon with the journey it has travelled towards racial equality. It discovers that while progress has been made, the distance it has travelled from the past, from the original sin of slavery, is much shorter than the road ahead. Each generation of African Americans is given no choice but to renew the struggles of previous generations against America’s racial degeneracy.

America’s racial backwardness is marked and sustained by cowardice, the complicity of the wider society in its perpetuation, the cognitive inability to take race and racism seriously, the political refusal to address it systematically, the obliviousness of too many people to its destructiveness not only for its victims but also its perpetrators and beneficiaries. Racism diminishes the entire society, robbing it of its citizens’ full human potential; it leaves in its trail horrendous wastage of human resources and lives.

America’s failure to have a concerted conversation on race and racism is not surprising for too much is at stake for too many people, interests, and institutions. But racism will not disappear by ignoring it, dismissing it, or wishing it away through fanciful invocations of a postracial society or misguided censure against political correctness. Failure to address it will continue to erode the moral, political, and constitutional fiber of the nation, and make it a global laughing stock for the glaring mismatch between what it preaches abroad and practices at home.

At the height of the Cold War and decolonization, the United States lost hearts and minds in Africa, Asia, and Latin America because of the racist treatment of its black citizens. In today’s era of changing global hegemonies marked by the rise of the rest in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, the ancestral homelands of America’s minorities, images beamed from American cities of police violence against people of color diminish the country’s global soft power that it so badly needs as its hard power erodes. A serial domestic abuser cannot expect to be respected by its neighbors aware of such abuse, as is the case for America in today’s world of hyper connectivity.

In so far as we are all raced, race and racism is our collective problem. It is not a black problem. It is an American problem. We must find the courage and the honest language to address it with the seriousness it deserves in all aspects of our lives at the individual, interpersonal, institutional, community, national, and global levels. Only then will the problem of the color line of previous centuries cease to be a problem for future generations, and can we begin to fully realize the possibilities that lie in the indivisible and interconnected mutuality of our collective humanity to build truly democratic, inclusive, and humane societies.

This is what the lives, tragic deaths, and memories of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Eric Garner, and Tamir Rice, and countless others before and since mean to me: the imperative that, as we say in Southern Africa, the struggle for liberation continues, for our liberation as peoples of African descent from centuries of Euro-American racism, and for the humanization and democratization of our countries in the diaspora and the world at large.