When Malcolm X went to Africa

"As long as we think that we should get Mississippi straightened out before we worry about the Congo, you’ll never get Mississippi straightened out."

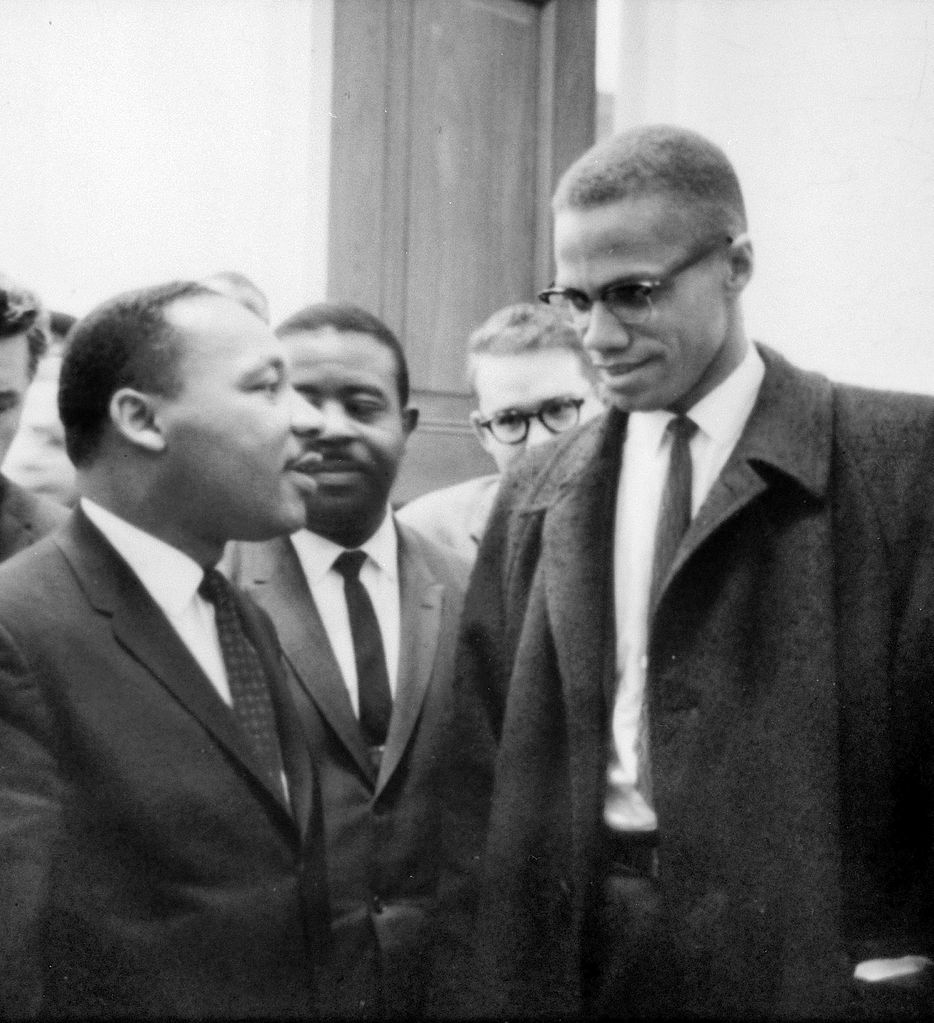

Martin Luther King Jnr. and Malcolm X (Wiki Commons).

I am dipping in and out of Manning Marable’s 600 plus-page biography of Malcolm X. As Tariq Ali, correctly writes in The New Left Review (in a review of the book), there’s too much on Malcolm X’s personal life so that as a result “… the events that shaped his continuing intellectual evolution—the killing of Lumumba and the ensuing crisis in Congo; the Vietnam War; the rise of a new generation of black and white activists in the US, of which Marable was one—are mentioned only in passing.”

As we know Malcolm X made at least four trips to the continent–the first in late March-early April 1959 and then again 2 months later and, finally, two trips in 1964. In 1992, the Christian Science Monitor interviewed W.E.B. du Bois’s grandson, David, a journalist who lived in Egypt and welcomed Malcolm to Cairo in April 1964: “The important thing to an African-American is the mass accumulation of human beings of color, in which white folks are a minority – a precise and distinct minority; the brotherhood, the oneness of experience.”

Speaking one month later, in May 1964, to students in Accra, Ghana, Malcolm X spoke of the welcome he received in Nigeria:

“When I was in Ibadan at the University of Ibadan last Friday night, the students there gave me a new name, which I go for — meaning I like it. “Omowale,” which they say means in Yoruba — if I am pronouncing that correctly, and if I am not pronouncing it correctly it’s because I haven’t had a chance to pronounce it for four hundred years — which means in that dialect, “The child has returned.” It was an honor for me to be referred to as a child who had sense enough to return to the land of his forefathers — to his fatherland and to his motherland. Not sent back here by the State Department, but come back here of my own free will.”

He expressed support for Ben Bella of Algeria, Nasser in Egypt and his host, Kwame Nkrumah. He also had advice for the students:

“… [M]y own honest, humble opinion is, anytime you want to come out from under a colonial mentality, let the government set up the educational system and educate you in the direction or way they want you to go in; and then after your understanding is up to the level where it should be, you can stand around and argue or philosophize or something of that sort.”

In the May/June 2011 issue of New Left Review, the British-Pakistani writer, Tariq Ali, reviewed Manning Marable’s book about Malcolm X, Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention. It is worth quoting Tariq Ali’s summary of Malcolm X’s two visits to the African continent and its effect on Malcolm X:

“… What Malcolm had witnessed in Africa, meanwhile, gave more substance to his changing political views. Soon after his return, he gave a speech drawing parallels between European colonial rule and institutionalized racism in the US: the police in Harlem were like the French in Algeria, ‘like an occupying army’. As Marable notes, ‘for the first time he publicly made the connection between racial oppression and capitalism’. African-Americans should, he said, emulate the Chinese and Cuban revolutions, also observing that ‘all of the countries that are emerging today from under colonialism are turning towards socialism. I don’t think it’s an accident.’ …”

“Malcolm made a second, longer African trip from July to November 1964, visiting a string of countries where he met a range of intellectuals and political figures. In Egypt, he spoke at the OAU conference and talked with Nasser; in Ghana, he met Shirley DuBois and Maya Angelou; in Tanzania, Abdulrahman Mohamed Babu and Julius Nyerere; in Kenya, Oginga Odinga and Jomo Kenyatta. The international dimension was crucial to his thinking in the final months. In mid-December, he invited Che Guevara—in New York for the celebrated UN General Assembly speech—to address an OAAU rally; Guevara did not attend, but sent a message of solidarity. ‘We’re living in a revolutionary world and in a revolutionary age’, Malcolm told the audience. He continued: ‘I, for one, would like to impress, especially upon those who call themselves leaders, the importance of realizing the direct connection between the struggle of the Afro-American in this country and the struggle of our people all over the world. As long as we think—as one of my good brothers mentioned out of the side of his mouth here a couple of Sundays ago—that we should get Mississippi straightened out before we worry about the Congo, you’ll never get Mississippi straightened out.’… “

Malcolm X was assassinated on February 21, 1965.